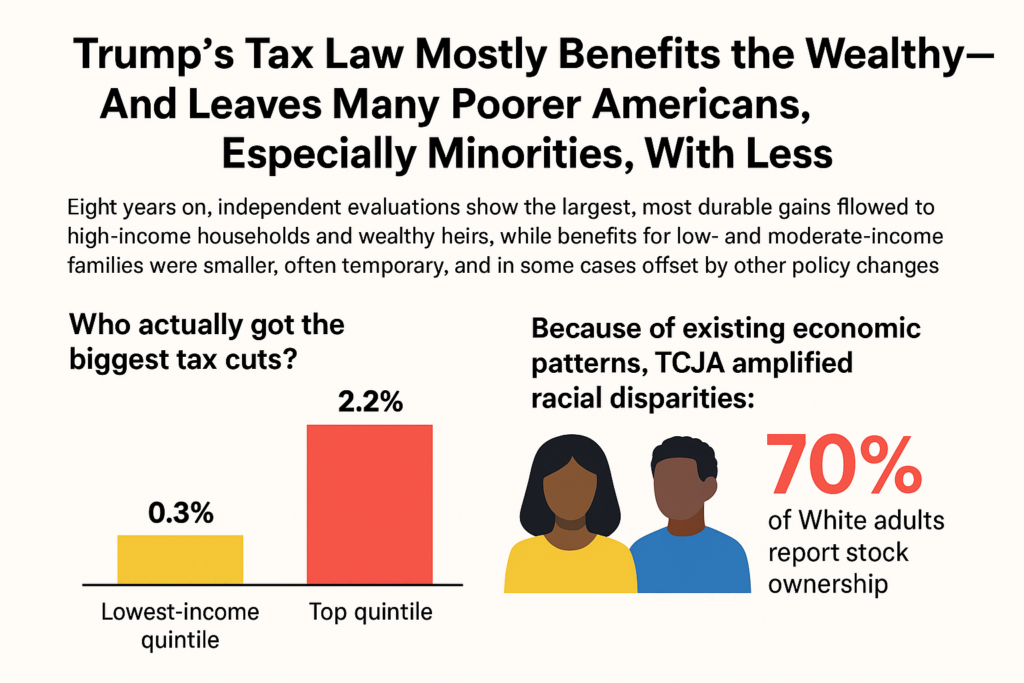

When the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) became law in December 2017, supporters promised a broad middle-class tax break that would “lift all boats.” Eight years on, independent evaluations show a different picture: the largest, most durable gains flowed to high-income households and wealthy heirs, while benefits for low- and moderate-income families were smaller, often temporary, and in some cases offset by other policy changes. Because of longstanding racial gaps in income, wealth, homeownership, and stock ownership, Black and Latino households captured a smaller share of the law’s upside—and face greater exposure to its downsides. (Brookings, Tax Policy Center)

Who actually got the biggest tax cuts?

Nonpartisan distributional analyses show TCJA raised after-tax incomes more (both in dollars and as a share of income) for higher-income households than for those at the bottom and middle. The Tax Policy Center estimated the individual provisions alone raised after-tax income by 0.3% for the lowest-income quintile versus 2.2% for the top quintile, with even larger gains for the 95th–99th percentiles. Brookings reached similar conclusions and warned TCJA is “regressive” and makes the income distribution more unequal. (Tax Policy Center, Urban Institute, Brookings)

Two design choices explain a lot:

- Permanent corporate cuts vs. temporary family cuts. TCJA cut the corporate tax rate from 35% to 21%—a permanent change—while many individual tax cuts (rate reductions, larger standard deduction) were set to expire after 2025. Corporate-focused benefits are captured disproportionately by high-income households who own more capital. (Tax Policy Center)

- Weaker estate tax. TCJA roughly doubled the estate and gift tax exemption (indexed for inflation) through 2025, shielding multimillion-dollar inheritances from tax and delivering benefits to the wealthiest estates. Congressional and independent summaries consistently note this change’s skew toward the top. (Tax Policy Center, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Congress.gov)

Why poorer Americans saw less—and sometimes nothing

Although many families received a tax cut in the early years, those gains were modest for the bottom and often eroded by offsets:

- Loss of personal exemptions and other changes blunted the value of the larger standard deduction for some households. Net gains for the lowest-income quintile were small on average. (Tax Policy Center)

- Child Tax Credit (CTC) design. TCJA expanded the CTC to $2,000 per child but restricted eligibility to children with Social Security numbers (SSNs)—excluding roughly a million previously eligible, largely in mixed-status immigrant families. Because very low-income families don’t owe enough income tax and the refundable portion is limited, many of the poorest children still do not receive the full credit. (Congress.gov)

How these choices hit minorities harder

Because tax laws interact with existing economic patterns, TCJA amplified racial disparities in several ways:

- Wealth & stock ownership. High-income and wealthy households gain disproportionately from corporate tax cuts via higher after-tax profits and asset prices. White households are far more likely to own stocks and mutual funds than Black or Hispanic households, so they capture a larger share of corporate-driven gains. Recent Gallup polling shows about 70% of White adults report stock ownership, compared with 53% of Black adults and 38% of Hispanic adults. (Gallup.com)

- Homeownership & itemized deductions. Tax subsidies tied to homeownership (like the mortgage-interest deduction) tend to benefit those who own homes and itemize. Homeownership rates remain markedly lower for Black and Latino households, limiting access to these subsidies and dampening their tax benefits relative to White households. (Eye On Housing, Census.gov)

- Estate tax changes and intergenerational wealth. Doubling the estate tax exemption primarily benefits the heirs of very wealthy estates—disproportionately White because of the racial wealth gap. Weakening this tax eases large wealth transfers at the top and widens the wealth divide over time. Analyses by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) and partners conclude TCJA “supercharges” the racial wealth gap by rewarding existing wealth advantages. (Congress.gov, itep.sfo2.digitaloceanspaces.com, ITEP)

- Tax system features that miss many Black taxpayers. ITEP’s research also shows Black taxpayers with similar profiles to White taxpayers still often pay more because the code favors benefits (like certain employer-provided perks and retirement vehicles) that Black workers are less likely to access due to structural barriers in the labor market. (ITEP)

- Limits on the Child Tax Credit. The SSN requirement added by TCJA excluded many U.S. citizen children in mixed-status families, disproportionately affecting Latino households. Because the CTC is only partially refundable, more than half of Black and Hispanic children live in families with incomes too low to receive the full credit under current rules—a design feature that blunts anti-poverty impacts for communities of color. (Congress.gov, Wikipedia)

Bottom line for communities of color

- Less access to the biggest tax advantages. The provisions that deliver the largest, most lasting benefits—corporate cuts, capital-income gains, and higher estate-tax exemptions—are tethered to asset ownership and large inheritances, which skew heavily toward White and higher-income households. (Brookings, Congress.gov)

- Smaller or conditional benefits from family-focused provisions. Many low-income families of color saw modest tax cuts early on, but limits in refundability and documentation rules meant the poorest children often received reduced support—or none at all. (Tax Policy Center, Congress.gov)

- Inequality effects compound over time. Because TCJA’s largest benefits build wealth at the top, they compound across years and generations, reinforcing the racial wealth gap measured in the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances and highlighted by Urban Institute and Brookings researchers. (Urban Institute, Brookings)

What policy fixes would help?

Experts across the spectrum have laid out options that would make the tax code more equitable for low- and moderate-income families and for communities of color:

- Make the CTC fully refundable and remove barriers that exclude mixed-status families, so the credit reaches the poorest children. (Congress.gov)

- Let the high-income individual and estate-tax cuts expire on schedule (or reverse them), while focusing new relief on low- and middle-income households. (Congress.gov, U.S. Department of the Treasury)

- Target asset-building (matched savings, first-generation homebuyer credits, and retirement coverage for workers without plans) to close gaps in wealth-producing assets. (Urban Institute)

The takeaway

TCJA’s structure channeled the biggest, most durable gains to high-income households and wealthy heirs. Because of entrenched disparities in income, wealth, and access to tax-favored assets, Black and Latino families captured less of the upside—and more of the risk that temporary benefits fade while inequality deepens. An equity-focused reform agenda would redesign family benefits to reach the poorest children, curb windfalls at the top, and invest directly in closing racial wealth gaps. (Brookings, Tax Policy Center)

More Stories

One Dead, Two Injured in Shooting Near ASU Campus

ICC Judges amend the Regulations of the Court to regulate motions for acquittal

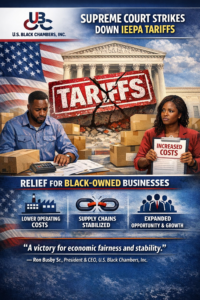

U.S. Black Chambers, Inc. Statement on Supreme Court Decision Invalidating Tariffs Imposed Under IEEPA