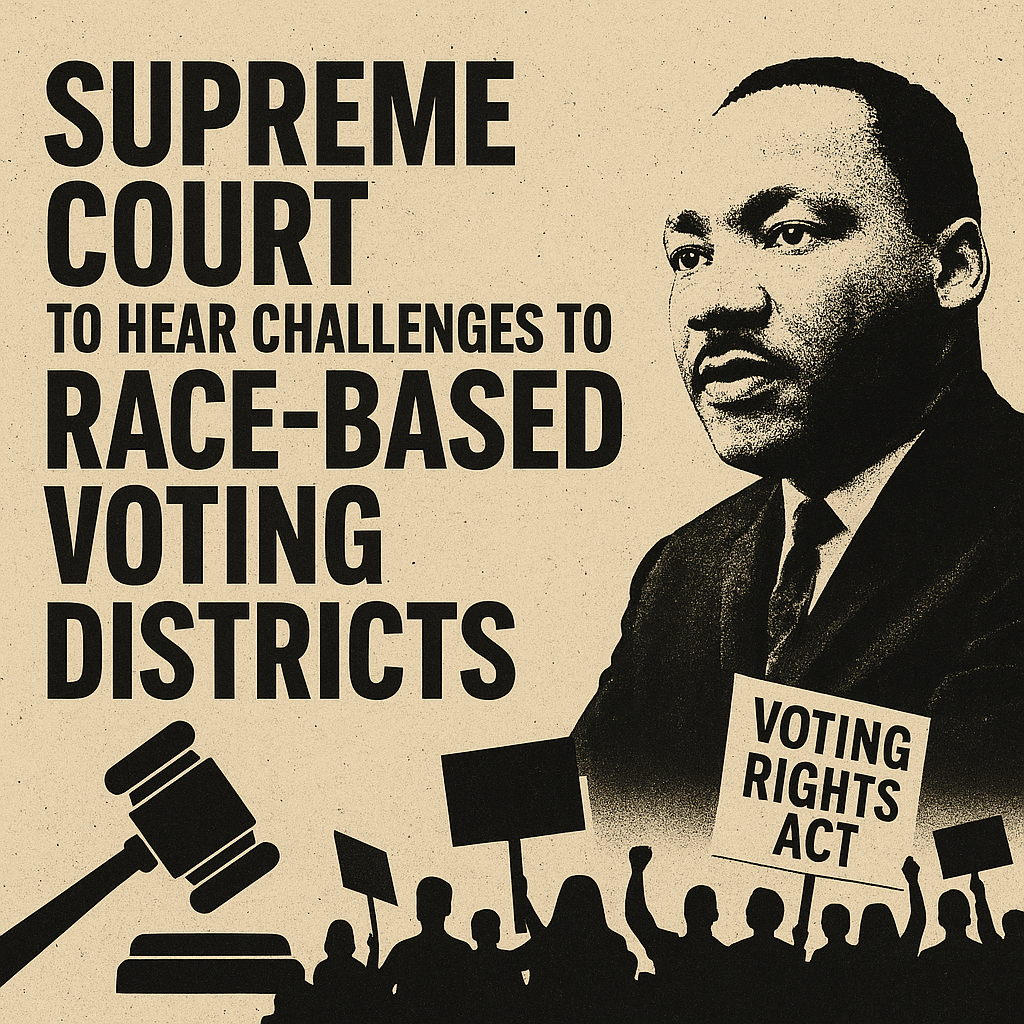

In a forthcoming decision, the Supreme Court appears poised to curtail key protections of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) — the very law for which so many marched, bled, and died. The Washington Post+2Brennan Center for Justice+2

A Brief History of Hard-Fought Gains

The Voting Rights Act was enacted to enforce the right to vote guaranteed by the 15th Amendment, particularly in jurisdictions with histories of overt racial discrimination. Department of Justice+1

During the civil rights era, figures such as Martin Luther King Jr. and thousands of activists challenged poll taxes, literacy tests, intimidation at the ballot box, and other mechanisms designed to suppress Black and Brown votes.

One of the key tools the VRA provided was the ability to challenge maps and districts that diluted the voting power of minority communities (“vote dilution”) — for example, by “packing” minorities into a few districts or “cracking” them across many, so their cohesive electoral influence is weakened. Columbia Law Review+1

What the Court Is Considering Now

At issue in the upcoming case (involving Louisiana) is whether a district drawn to include a majority-Black population is constitutionally permissible, and whether the VRA’s Section 2 — which prohibits electoral practices that dilute minority votes even without explicit discriminatory intent — remains valid in its current form. ABC News+1

The conservative justices have raised concerns that race-conscious districting may violate the Equal Protection Clause if race is the predominant factor. Some have argued that the use of race should have an endpoint or be phased out. PBS+1

In short, A law created to protect racial minorities from having their votes diluted is itself now under threat from the very court that is tasked with enforcing constitutional equality.

Why This Matters in the South

States in the American South historically engaged in systematic exclusion of Black voters from meaningful representation — through Jim Crow laws, literacy tests, poll taxes, intimidation, and gerrymandering.

In many southern states today, Black and brown populations make up a substantial part of the electorate, yet representation has often lagged. When district lines are drawn to intentionally dilute or ignore minority voting strength, the political power of these communities is diminished.

If the Supreme Court limits the ability to draw majority-minority districts (or forces a higher bar to justify them), then the power of Black and brown voters to elect their candidates of choice may be substantially reduced — especially in states where one party controls the map-drawing process and where racialized voting patterns persist. Civil-rights watchers warn that rolling back or weakening Section 2 would sharply reduce minority representation. Brennan Center for Justice+2State Court Report+2

The Argument Made by Opponents of Race-Based Districts

Supporters of eliminating race-based districting argue:

-

That using race explicitly in drawing maps is itself a form of racial classification that runs counter to a “color-blind” interpretation of the Constitution. PBS

-

The remedy of majority-minority districts may no longer be justified because conditions have changed (e.g., registration and turnout of minorities have improved), and so race-based remedies should be phased out or reconsidered. Democracy Docket+1

-

That requiring states to create majority‐minority districts gives an unfair advantage to one party (often the Democratic Party, since minority voters tend to support it) and thus shifts redistricting from racial fairness to partisan advantage. Vox+1

Why the Concerns Are Intense

The danger is two-fold:

-

Suppose the Court holds that race cannot be a predominant factor even when trying to remedy historical discrimination. In that case, map-drawers will have more freedom to draw districts that dilute minority power under the guise of being “race-neutral.”

-

If Section 2 is substantially weakened or invalidated, the federal backstop against discriminatory maps disappears. States with majorities or one-party control will have fewer constraints, and minorities may be left to state courts or patchwork protections, which historically have been inconsistent. State Court Report

In the South — where Black populations often hover around 20-40 % in certain states, yet statewide representation has remained minimal — the impact could be profound. Maps that once created a single Black‐majority district might be converted, or the threshold for creating them raised. This could mean fewer Black districts, fewer Black representatives, fewer statewide officials, and fewer opportunities for Black and brown communities to set policy or hold power.

What the Decision Will Mean for Democracy

If the Court rules to limit or eliminate the ability to draw race‐conscious districts:

-

Minority voters may see fewer “safe” or “opportunity” seats where they can elect candidates of their choice.

-

Political power may shift more fully to the majority party in each state, reducing competitive districts and minority leverage.

-

The exclusion of race as a factor may disproportionately benefit areas where racial blocs vote in a predictable way (e.g., Black voters supporting one party), enabling map-drawers to lock in partisan advantage under a veneer of “neutrality.”

-

Federal enforcement of voting rights through Section 2 may become so weak as to be ineffective, leaving the field to local/state litigation, which is uneven and under‐resourced.

The Moral and Historical Dimension

For decades, the civil rights movement fought not only for the right to register and vote, but for meaningful representation. Activists marched for laws like the Voting Rights Act because formal equality was not enough without political power. Many believed that the ballot box and the election of representatives of choice were essential to dismantling structural racism in the South — educational inequalities, segregation, under-investment, and political exclusion.

To see the law that was one of the movement’s crowning achievements under threat may feel like a betrayal of those sacrifices. The argument that “we don’t need race-based tools anymore because racism is solved” ignores the lived reality of structural racism: socioeconomic inequities, racial polarization in voting, and map-drawing processes that still often reflect the old order.

What Can Be Done

-

Civil-rights groups will need to prepare for a post-Section 2 world: state legislation, state constitutional protections, and more local advocacy may become more important than ever.

-

Data collection on racial polarization, turnout, and representation will be critical to demonstrate ongoing disparities.

-

Engaged minority communities must continue voter registration, turnout efforts, and candidate training — because representation cannot be assumed.

-

Advocacy for transparency and fairness in redistricting at the state level requires public oversight, independent commissions, and perhaps federal statutory reform if Congress acts.

-

Public awareness is key: Many may not realize how map-drawing still affects who gets elected, whose voice is heard, and what laws get passed.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s forthcoming decision over districting by race is not just a technical matter of map lines — it is a decision about the future of political power, representation, and civil-rights law in America. If the protections of the Voting Rights Act are diminished, the promise of equality at the ballot box risks being hollow — particularly for Black and brown communities in the South who have historically been excluded from fair representation.

In effect, this moment may determine whether the hard-won gains of the civil-rights era are secured for future generations — or whether they are once again eroded under new legal theories of “neutrality” that ignore persistent racial inequities.

More Stories

One Dead, Two Injured in Shooting Near ASU Campus

ICC Judges amend the Regulations of the Court to regulate motions for acquittal

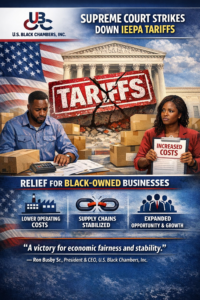

U.S. Black Chambers, Inc. Statement on Supreme Court Decision Invalidating Tariffs Imposed Under IEEPA